1997: Georges Adéagbo

What if modern art actually grew out of contemporary art? What if the end came at the beginning? And what if it were art that created the artist? Georges Adéagbo says that “first of all you have to discover what an individual’s origins are and only then can you start talking about the individual themselves”. Since around the time the Jimmie Durham and David Hammons exhibitions were held at Friart in 1993, the issue of postcolonialism has occupied an ever-larger space in contemporary art. The term “origin”, to which Adéagbo refers, has often, according to him, become clichéed. Critical of western consumerism, injustices and the hybridity present in discourse stemming from colonialism, Georges Adéagbo makes most of his works in situ, gathering together and collecting objects that he then brings to the place in which his work is presented. For Adéagbo, humanity is constantly trying to bring about change in the world without wanting to assume the consequences. Humanity and its different cultures are assembled, recombine and are dismantled, just like the installations and accumulations of Adéagbo’s objects and the visitors to his exhibitions.

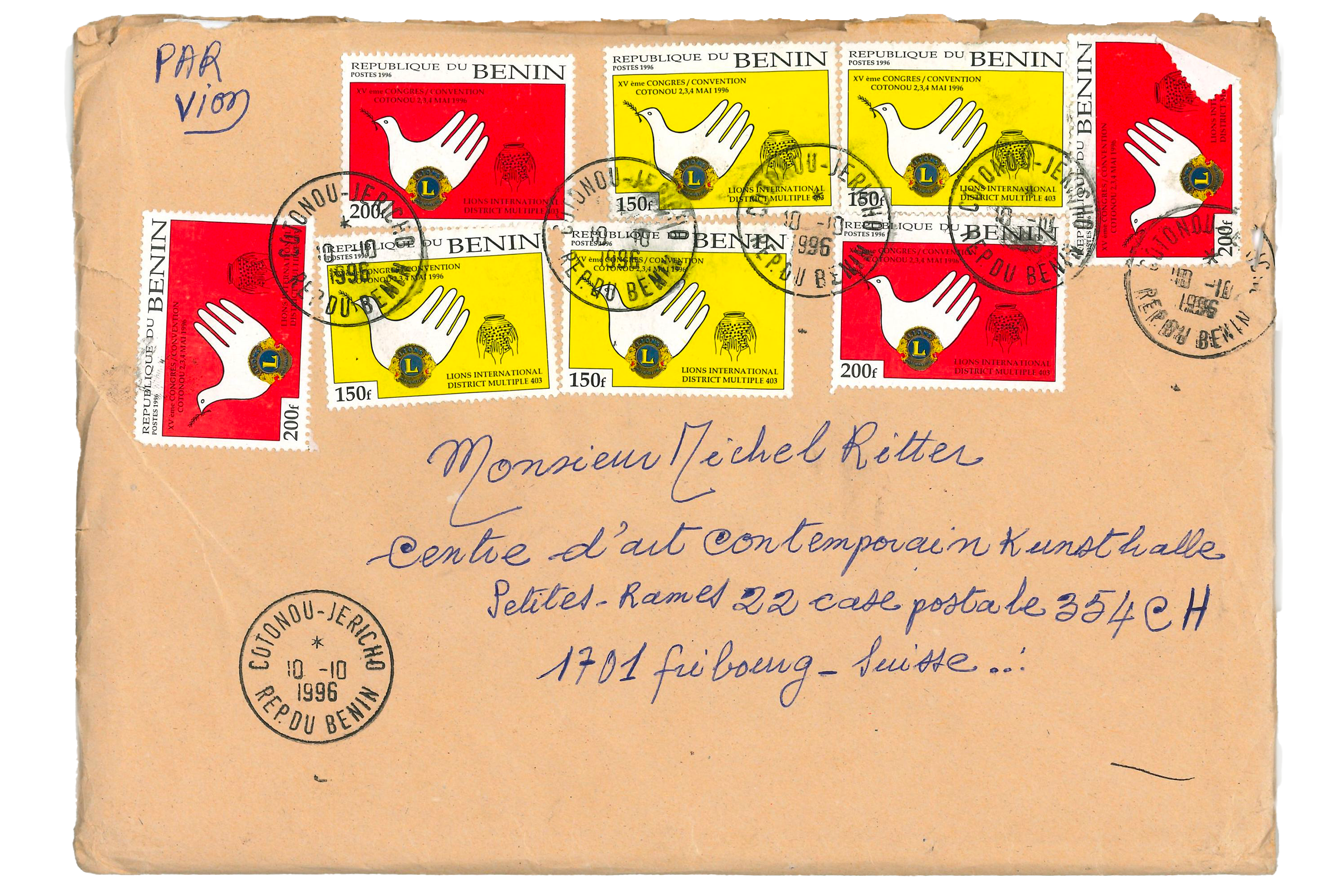

An archeologist of universal thought, Georges Adéagbo is an African artist born in Benin who does not see himself as an artist. Speaking of himself in the third person, “[his] Georges persona” wonders how the world sees the history of Africa today. His work consists in assembling information to provide us with potential avenues of enquiry. The objects and fragments that make up his artistic installations are diverse but always relate to Adéagbo’s history and sensibility. He assembles paintings, books, CDs, annotated photocopies, clothing, bags etc.

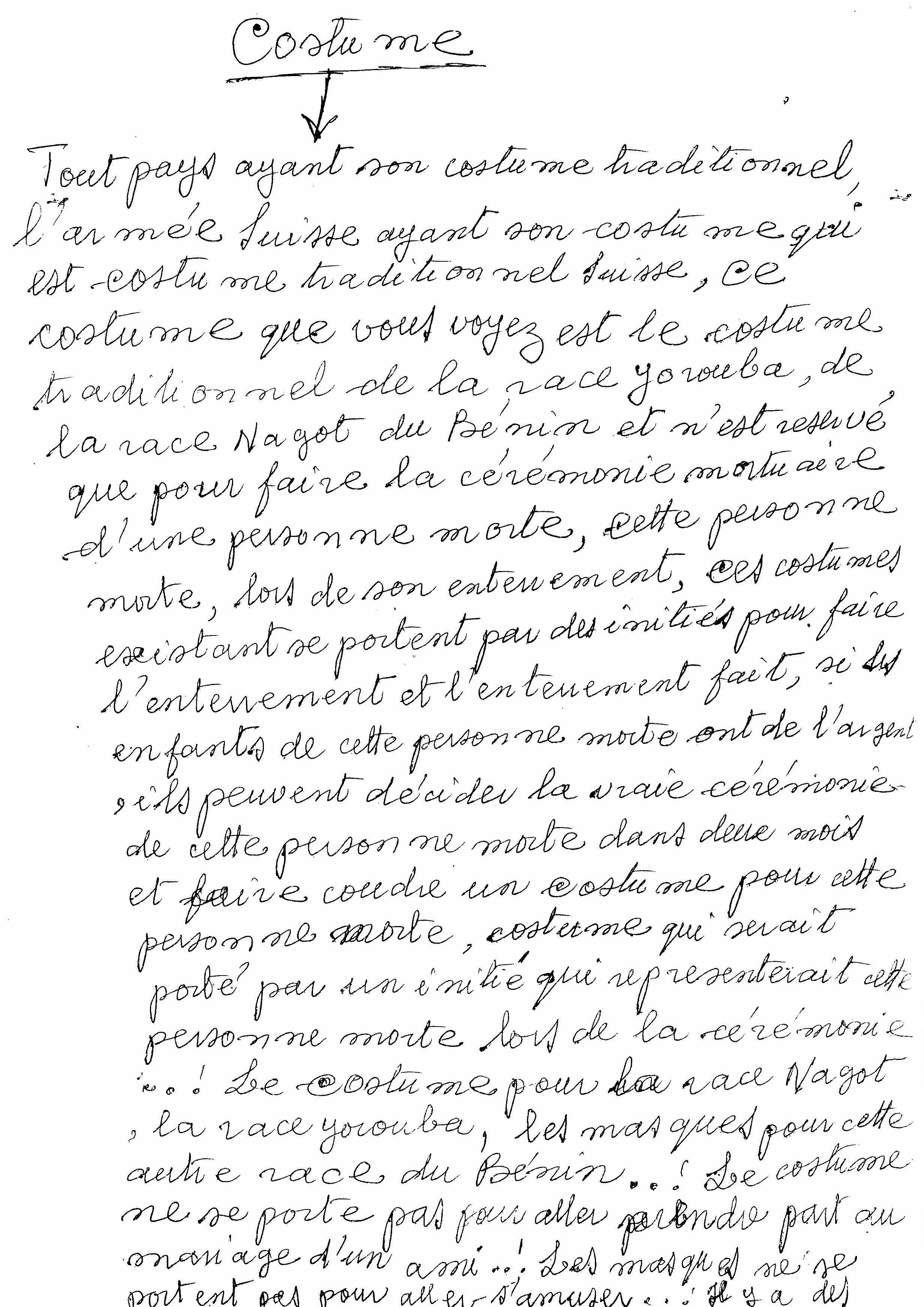

In his exhibition at Friart from 26 January to 23 March 1997, Adéagbo presented his found and collected objects. The artist used the Ash Wednesday custom of clearing one’s house of useless objects. He collected newspapers such as La Liberté and Le Matin, the Belluard Festival programme, plastic bags, packets of cigarettes… He also integrated discoveries of more personal objects such as writing on Benin. One of the centrepieces of his exhibition was the traditional costume of the Yoruba community, a piece of clothing reserved for funeral ceremonies that Adéagbo contrasted with a Swiss military uniform used for other purposes.

Thrown into the limelight by Dialogues of Peace, the exhibition organised par Adelina von Fürstenberg for the fiftieth anniversary of the United Nations, Adéagbo would become the first African artist to receive the Grand Jury Prize at the Venice Biennale in 1999, before showing his work at Kassel’s Documenta 11 in 2002. In his work, visitors are constantly called on to put themselves in the place of the other and meditate on the past and the constant changes and developments that the world faces: what if the end really did come at the beginning?

Text written in collaboration with Tania Siegenthaler, presented as part of the exhibition Friart est né du vide. L’esprit d’une Kunsthalle, MAHF Museoscope, 27.08 – 17.10.2021.

Translation: Jack Sims