Michel Ritter and art in the Nineties at Friart

This article gives an overview of how Friart programming integrated developments on the international art scene during the institution’s first decade of exhibitions, under Michel Ritter’s direction, from 1991 to 2002. It is also a synthesis of research carried out in collaboration with the University of Fribourg during the 2021 spring semester, which took the form of a seminar on the history of contemporary art. (1)

After ten years without a physical home and negotiations with the town hall, premises were made available to Friart Association by the Fribourg authorities in November 1990, with financial support provided from the state for the space to put on exhibitions. (2) In setting up in the building at Petites-Rames 22, Friart became a Centre d’art. (3) Under the direction of Michel Ritter, between 1991 and 2002, the Kunsthalle forged a strong identity on the Swiss artistic landscape. By 2000, the Friart programme was seen by many peers, professionals and institutions as one of the most, if not the most, compelling in Switzerland. Friart was where most risks were taken, where artists were discovered earliest and where daring formats were put forward, not somewhere that simply based its choices on market trends. (4) In a town at the crossroads of the linguistic regions and of secondary significance in terms of the national urban fabric, an alternative style and narration was taking form. In the memories of those who were part of the adventure, the Friart signature always bore an imprint that owed a great deal to the individuals involved, compensating the lack of financial resources and its peripheral geographical positioning: Friart and its curator Michel Ritter were seen as being closer to artists (5) (ill. 1 et 2).

In the course of the 1990s, the Kunsthalle supported the emergence of numerous artists who were fully engaged in the construction of what became a canonical history. It was constructed around categories of globalised art, contextual art, postcolonial thinking, relational aesthetics and technological change. An ideal synergy came into being between this new, ambitious art space and these developments. Both had in common an affirmation of the experiential dimension by means of which art is approached as an apprehension of the real as against the fetichism of the object. Friart exhibitions were envisaged as encounters with the visitor(s) in which the “method of presentation constitutes the key part of the work”. (6) The practice of these artists was interpreted by means of theories imbued with cultural studies, echoed in circles detached from pure academic constraints, a lexicon of research and experimentation flourishing in actuality in a kunsthalle that did not however overly trouble itself with theoretical justifications. Friart was more than a space for the reception of these practices. After the alternative period in the 1980s during which it had no permanent base, Friart contributed to the development of a perspective whereby contemporary art took the form of a means of reflection on the world, an area of possibilities whose horizon remained blurred. Contemporary art was not yet fully part of the cultural ecosystems of small towns. Friart had to win over an audience, gain its legitimacy and give itself a license to claim, de facto, its status as an experimental domain within the cultural landscape:

“The challenge, in terms of perception of different current artistic practices, comes essentially from the difficulty we have in understanding these practices, even though art is increasingly quotidian in the way it refers to day-to-day life and uses strategies from other disciplines (sociology, sciences, fashion, music, etc.).” (7)

SWISS NETWORK / INTERNATIONAL NETWORK

“Museums and galleries are not places to relax. Information from outside, from outside the front door, has to be brought in.” (8)

In 1991, after the Jacques Thévoz exhibition, Michel Ritter set to work on the first years of programming, which in part drew on relationships developed over the decade of itinerancy. He invited artists and friends from the Swiss art scene: Bruno Baeriswyl (1991), Ian Anüll (1992), Roman Signer (1992). Large exhibitions of Swiss artists were to become a Friart trademark, often giving these artists their first institutional presentation, which is something that constitutes an important step in the career of an artist. Without being exhaustive, we can cite the Francis Baudevin (1991), Raoul Marek (1991) and Alain Huck (1993) exhibitions, or Thomas Hirschhorn’s and Valentin Carron’s important first exhibitions in Switzerland (Très grand buffet (1995) and Sweet Revolution (2002) respectively) (9) (ill. 3).

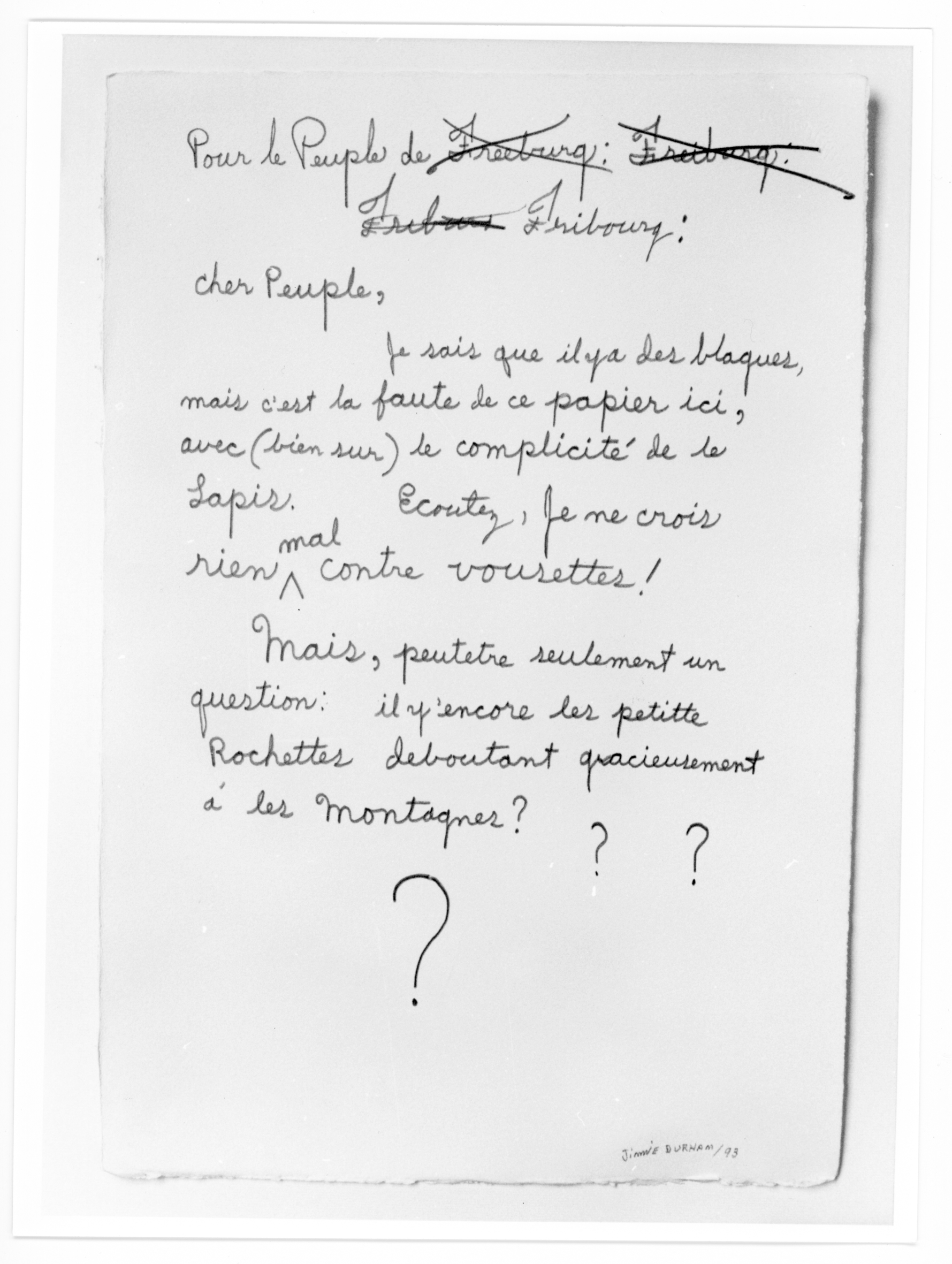

The 1990s in Switzerland were marked by a movement of public recognition for contemporary art. (10) In its globalised version, the cultural expansion of art was manifested in the creation of an international calendar of biennales and fairs. In 1993, two artists who had been part of the 1992 Documeta IX exhibited at Friart in collaboration with the Belluard Bollwerk International performance festival. David Hammons, an important Afro-American artist, came to spend a week in Fribourg to create works on site. Cherokee artist Jimmie Durham didn’t travel in person but created a series of drawings to accompany his works in a playful reference to Swiss language and topography (ill. 4).

CLOSE LINKS BETWEEN GALLERIES: PAT HEARN, AMERICAN FINE ARTS, CHRISTIAN NAGEL

A network of emerging galleries became concentrated in an ever-smaller number of artistic capitals. Communication was by fax. Prints of photos of works taken with film camera circulated and served as portfolios. You found out what was going on by obtaining invitation cards sent by post and specialised magazines. (11) You would travel to attend other openings, fairs and exhibitions. The artist become curator Michel Ritter was connected to figures involved in the renewal of a scene that was gravitating around districts in Lower Manhattan that were undergoing gentrification (Pat Hearn and American Fine Arts (Colin de Land)) and the city of Cologne, in particular through the gallery Christian Nagel. These spaces supported the same artists at the time. They helped create a community of interests and dialogue on American institutional criticism and European contextual art.

For his exhibition Tour de Suisse (1994), Swiss artist Christian-Philippe Müller (ill. 5), who exhibited at the gallery Christian Nagel, presented the results of a filmed survey based on a series of visits to directors of Swiss artistic institutions. A questionnaire inspired by sociology of art as developed by theoretician Ulf Wuggenig (12) constituted a particularly salient example of contextual art. The figure of the artist investigator reappropriating the social sciences and/or drawing on post-structuralist discourse or cultural studies began to emerge. American artist Mark Dion presented his work in equal proportions at Nagel in Cologne and the American Fine Arts gallery in New York. He would be invited to Friart several times. In a collective exhibition in 1992, he collaborated with the Natural History Museum, at the same time as he, himself, was investigating the flora and fauna of Brazil. For his solo exhibition Unseen Fribourg (1995), he amassed several cubic metres of earth taken from two distinct parts of the town and extracted, documented and exhibited, from one, living invertebrate organisms and from the other, fragments of debris of the civilisation above ground. The dramatization of the processes of production of scientific knowledge deliberately conflated the disciplines of natural sciences and archaeology to highlight the way in which knowledge always comes from a certain perspective and is never objective.

In 1996, Michel Ritter invited the American artist Renée Green to Friart. Müller and Green showed their work in the same galleries. Renée Green suggested to the curator that they get to know each other better through an exchange of letters, a practice that ran counter to the acceleration of communication technologies then underway. This search for authenticity helped better deconstruct her methodology and beliefs through the reassertion of an object representing the fantasy of the singularity of place: the post card (ill. 6). She proposed to show, in a temporary cinema installed on the first floor of Friart, films of Swiss filmmakers exploring the United States, or of the image of America they presented. Green’s work involves a reflection on the media apparatus, but always combined with an anthropological reflection on culture and the construction of identity.

NEW TECHNOLOGIES / NEW GENERATION ?

Reflection on new medias and their place in art marked both the 1990s and Friart programming. For Flow (1996), Renée Green created an internet site; Dominique Gonzalez Foerster, Zone de tournage (1996) (ill. 7) used live camera broadcasts and presented a CD-rom. Julia Scher put Fribourg under surveillance in Fribourg sous surveillance (1996) by installing cameras at strategic points around the town and broadcasting these images on screens in Friart. The end of the 1990s saw the progressive emergence of new impulses that were the reflection of artistic trends then under discussion in France. A new generation of artists was affirming a poetic of the everyday that nonchalantly and uninhibitedly mixed research on the prolix climate of mass consumption, the omnipresence of fashion in the development of an aesthetic of existence, the influence of the virtual universe and the future scenario of capitalism. These practices came to be referred to as relational aesthetics. (14) Olivier Zahm and his exhibition Fashion Video (1998), Jens Haaning and Super Discount (1998), Surasi Kusolwong and Everything 2 Francs (2001) all exhibited at Friart. The programme for Friart’s 10th anniversary in 2000 was given over to a new generation of in vogue exhibition makers. The relational aesthetic was notably represented by figures such as Olivier Zahm, Nicolas Bourriaud and Hans Ulrich Obrist. The programme was supplemented with invitations to Swiss curators Véronique Bacchetta, Lionel Bovier and Esther Eppstein, as well as the exhibition for the Swiss Art Awards for the year 2000.

Since its beginnings, the Kunstalle has chosen events with the aim of bringing vitality to its programme and involving approaches from other arts (architecture, fashion, electronic and experimental music, cinema etc.). At the moment when digital technologies, the mobile telephone and the internet found a place in people’s lives, the TECHNOCULTURE [Computer World] (1998) project involved young people who identified with electronic music subcultures. Faithful to the ideal of going there where things were coming into being, Michel Ritter called on local collectives who had taken part in the life of the Kunsthalle as technicians and for the organisation of exhibition opening night parties, which themselves were influenced by relational aesthetic trends. Here I’m thinking of the DJ collective DTP and of the PAC collective, which staged what must be my own first memory of an instance of contemporary art: being given a coffee and a croissant early in the morning between the train station and Collège Saint-Michel, on my way to another day’s lessons at school.

Text: Nicolas Brulhart

Translation: Jack Sims

(1) Many thanks to Prof. Dr Julia Gelshorn and the students who took part in what was an unusual project, whose aim was to enrich and facilitate the dissemination of what we know about the rich history of Friart by going through the fragmentary archives and including them in a general history of contemporary art.

(2) The first request for support made to the Fribourg authorities for the provision of premises dates from 1982. A positive response came in 1987 with the freeing up of a space previously used as a homeless shelter at Petites-Rames 22 in the Neuveville district. These premises, used at the time by the Fribourg billiard club and an amateur painter’s association would be transformed into an exhibition gallery in the autumn of 1990 and opened to the public on 25 November 1990.

(3) The term centre d’art is French. It refers to the development of spaces facilitating artistic production supported by the state since the 1980s. This notion is more recent that than that of the kunsthalle, which is a German concept and dates from the 19th century. The fact that Friart is at the crossroads of linguistic regions and their respective cultural influences explains why the institution has used both terms since its beginnings without necessarily taking their respective genealogies into account.

(4) This is a synthesis of the most noteworthy points made by experts consulted during the audit of 2000 with respect to the relevance and lack of financing received by the centre d’art.

(5) In the introduction to the 1992 Friart catalogue, Michel Ritter thus put forward a programme that he described as “very much in line with my own artistic sensibility”. In the 1994 introduction, he stated that he worked more by “intuition than by reference to theories that are inappropriate to the situation or not yet defined.”

(6) RITTER Michel: ‘Introduction’, Catalogue Fri Art 1996, p. 5

(7) RITTER Michel: ‘Introduction’, Catalogue Fri Art 1991, p. 4

(8) RITTER Michel: ‘Introduction’, Catalogue Fri Art 1993, p. 4

(9) All these artists were male. This reflects a problematic reality of cultural institutions of the time. Michel Ritter noted his regret in this respect in his introduction to the 1993 catalogue summarising the year’s activities. In 1996, the Friart programme would be made up solely of exhibitions of work by women.

(10) The organisational mission of European institutions thus came to be designated by the term New Institutionalism. See KOLB Lucie, FLÜCKIGER Gabriel (ed.), OnCurating, Issue 21, December 2013.

(11) From this generation, mention can be made of the importance, for England, of the magazine Frieze, founded in 1991, for Germany of Texte zur Kunst, founded in 1990, and for France of Purple or Documents sur l’art, founded in 1992.

(12) VON BISMARCK Beatrice, STOLLER Diethelm, WUGGENIG Ulf (ed.), Games, Fights, Collaborations - Das Spiel von Grenze und Überschreitung - Art und Culture Studies in the 90ies, Hatje Cantz, 1996.

(13) A Meter of Meadow on the ground floor of Friart exhibited the findings of 1m of earth taken from Lorette. History Trash Dig on the 1st floor exhibited the excavations of a rubbish tip from before the Second World War at Grabensall.

(14) See BOURRIAUD Nicolas, Relational Aesthetics, Les Presses du réel, Dijon, 2002