1981–1988: The Müller case

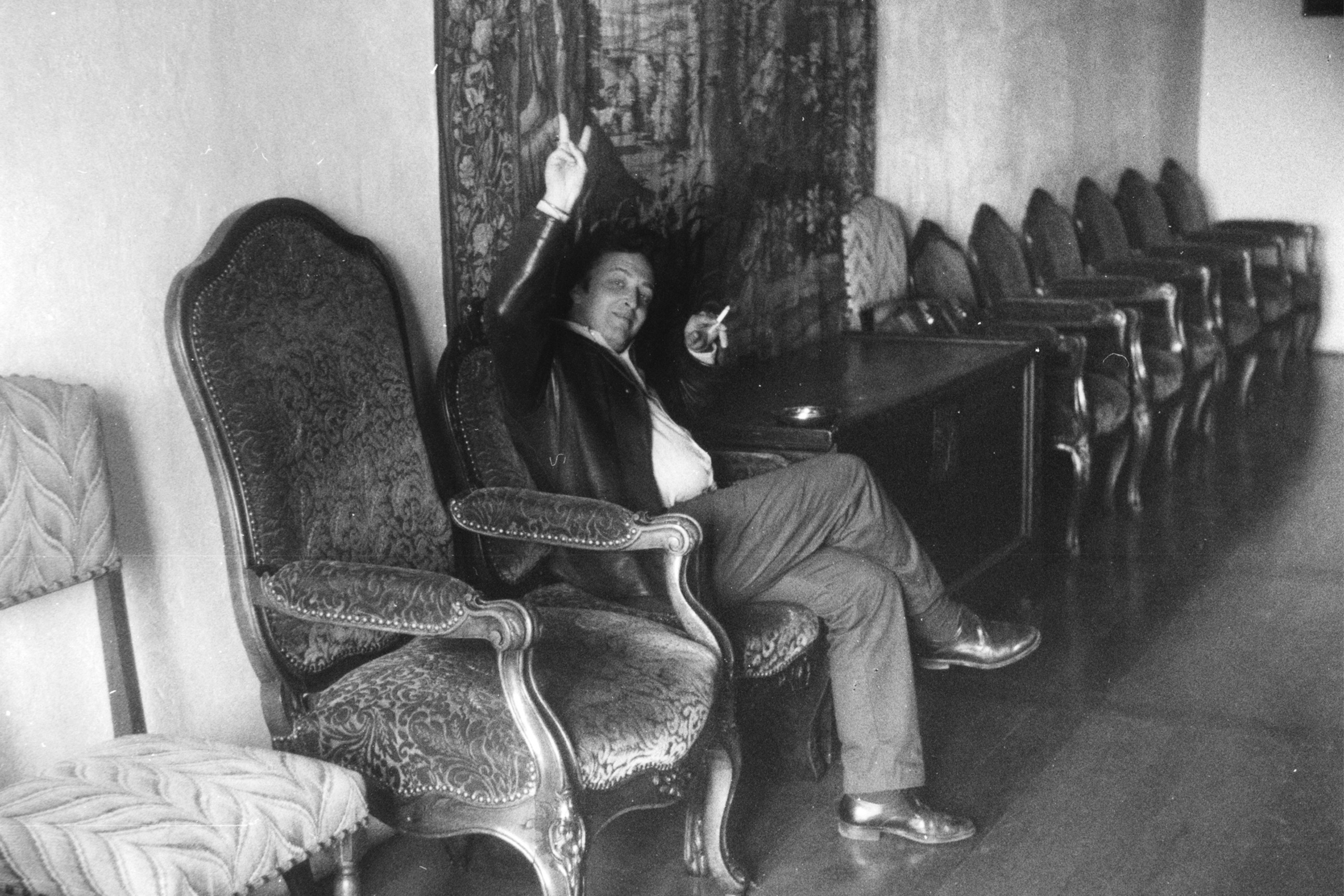

Josef Felix Müller was one of the artists commissioned to exhibit at Fri Art 81. He had been invited by Olga Zimmelova and, like the other artists, travelled to the exhibition space to allow himself to be inspired by the seminary building. He spent three nights in the three cells allotted him and then created three paintings that he named Drei Nächte, drei Bilder (Three nights, three pictures). These paintings however were never exhibited. They were confiscated by the canton police and stored at the Fribourg Museum of Art and History for many years. The confiscation was due to the erotic nature of the pictures, which were considered to be obscene. The reference in one of the paintings to the scene of Christ coming down from the cross provoked a strong reaction. Müller was in the habit of painting this type of image with sometimes disconcerting subject matter. According to him, the pictures symbolised “humanity” in its primitive state, letting its instincts loose.

Following the confiscation of the paintings, the organisers were found guilty of obscene publication, each receiving a fine of CHF 300. Assisted by lawyer Bernard Bonvin, they decided to appeal the case in March 1982. Pleading for them, Bonvin argued that the paintings did not constitute obscene imagery because, unlike pornography, they had not been created for commercial ends but rather were illustrations of a return to humanity’s primitive state. He insisted in particular on the fact that the image reminiscent of Christ had in fact no relationship with his coming down from the cross. The procurer, Joseph Daniel Piller, would not admit the relevance of the artist’s intentions. What was significant, according to him, was the impression made by these images on the average citizen who did not know Müller’s previous works.

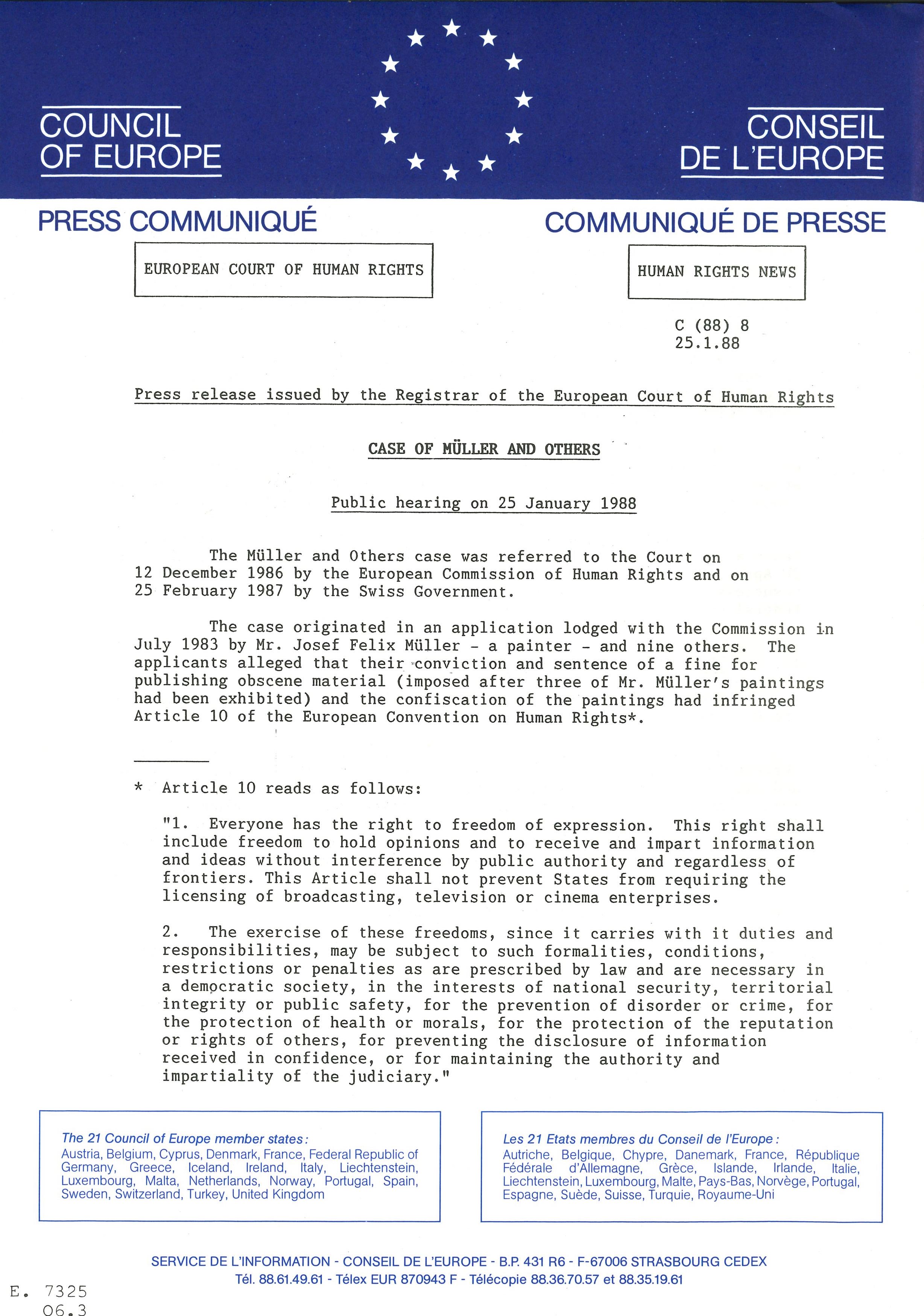

Paul Rechsteiner, a close friend of Josef Felix Müller’s, then took up the case. On 13 December 1983, he made an appeal to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. In 1985, the court declared the application made by Müller and the joint interested parties receivable. The case was transferred to the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe and the Swiss Government. In 1987, the Swiss Federal Office of Justice offered a deal: the paintings would be returned to Müller with costs paid as long as the accused withdrew their appeal from the European court. They refused the deal and the Strasbourg court hearing was set for 25 January 1988. Five days beforehand, the Sarine magistrate’s court ruled: “Not, it is true, without some hesitation, the court is of the opinion that the measure [confiscation of the three paintings] may now be lifted. This measure, it should be noted, was not unlimited but merely indeterminate in time, allowing a margin for a request for re-examination.” The European Court of Human Rights ruled to retain the Swiss court’s decision as the confiscation was no longer in force. The Swiss Confederation thus saved face. The paintings were returned but the claimants were condemned for obscenity. The fine was not returned and nor were they awarded trial costs. The case lasted eight years.

Walter Tschopp, one of Fri Art 81 ‘s main organisers, who had supported the artist throughout this period, wrote a detailed account of the case in issue 212 of Pro Fribourg, which served as the catalogue for the exhibition Friart est né du vide. L’esprit d’une Kunsthalle, MAHF Museoscope, 27.08 – 17.10.2021.

Translation: Jack Sims